The Myth of the Greedy Athlete

You'll hear a lot about "millionaire athletes." Don't buy it.

Sree’s newsletter is produced with Zach Peterson (@zachprague). Digimentors Tech Tip from Robert S. Anthony (@newyorkbob). Our sponsorship kit. The image above “athletes and money” was generated on Jasper.ai.

🗞 @Sree’s Readalong: We had our first-ever #ReutersReadalong today and our guest was Reuters Senior Correspondent Ernest Scheyder, author of “The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power our Lives.” You can see a recording here. You’ll find three years’ worth of archives at this link (we’ve been reading the paper aloud on social for 8+ years now!). The Readalong is sponsored by Muck Rack. Interested in sponsorship opportunities? Email sree@digimentors.group and neil@digimentors.group.

🤖 For just $10, you can buy the video and slides from my “Non-Scary Guide to AI” workshop and all-star panel with experts Aimee Rinehart, Senior Product Manager AI Strategy for The Associated Press; and Dr. Borhane Blili-Hamelin, AI Risk and Vulnerability Alliance, here: https://digimentors.gumroad.com/l/aipanel. One cool part is that it has Purchasing Power Parity pricing, so it adjusts automatically to the country you live in. eg: Sweden: $8; Italy: $6.70; Singapore: $6.60; UAE: $6.10; India: $4; South Africa: $4. TESTIMONIAL: "What an excellent class... thank you! Generative AI is an unbelievably exciting and terrifying subject. Looking forward to participating in future classes." — Jill Davison, global comms executive. · I am doing these workshops around the country and abroad as well as by Zoom, customized for each audience. If you'd like to discuss organizing one, please LMK at sree@digimentors.group

***

IT’S SUPER BOWL WEEKEND and somewhere there’s an uncle shaking his fist at the sky decrying “rich, spoiled athletes” who “should be grateful” for what they have. In reality, most of the people you’ll see play on Sunday are not, in fact, millionaires. Many of them have contracts that can essentially be canceled on a whim, more of them will not play professional American football past the next year or two, and all of them — even the very (very) well-paid ones — will have injuries that will hinder their lives for the rest of their lives.

I am a huge football fan (an addict, even), and I know there are way too many problems with the sport, but I watch anyway. I truly empathize with the role players, bench pieces, and practice squad guys who have their entire worlds riding on what happens over the course of a given Sunday for six months. Here are some tidbits you can use to dispel the myth of the rich, entitled athlete.

The average NFL career lasts just a bit more than three years. For running backs — a position that takes a remarkable amount of physical punishment — the average career is 2.5 years and the pay is among the lowest by position in the sport. If you’re a blue-chip recruit coming out of a major college program, you’ll get your first pro contract at 22 or 23 years old, and be out of the league by 25 or 26. This, after taking a beating at the hands of linebackers, defensive linemen and others who are absolute physical specimens — 6-foot-something, 200-250lbs of fine-tuned muscle, speed and power. It’s brutal and the science is becoming clear as day — playing football leads to lasting, often deadly brain damage in the form of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

This is from some new work from the Boston University CTE Center (yes, there’s a major medical field dedicated to it, that’s how bad it is):

Researchers at the Boston University CTE Center recently announced that they have now diagnosed CTE in the brains of 345 of 376 (91.7%) of NFL players studied.

By contrast, a 2018 Boston University study of 164 donated brains found one (0.6%) with CTE. The one CTE case was in a former college football player.

The NFL player data doesn't necessarily mean that 9 of 10 current and former NFL players have CTE. Exactly how many do is unknown since the condition can only be definitively diagnosed by brain autopsy after death.

Brains with CTE show a buildup of a protein called tau around the blood vessels. This is different from what is typically seen in brains affected by aging, Alzheimer's, or any other brain disease.

“Every 2.6 years of football at any level doubles your risk for CTE, and the longer you play and the higher level that you play, the greater your risk,” said Dr. Ann McKee, director of the Boston University (BU) CTE Center and chief of neuropathology at VA Boston Healthcare System. She also directs the UNITE brain bank, the world's largest tissue repository focused on CTE and traumatic brain injury.

The new research builds on findings from a 2017 study that showed CTE in 99% of the brains of NFL players, 91% of college football players, and 21% of high school football players in the UNITE brain bank.

In short, the earnings window is small, the odds of signing a multimillion-dollar deal are remarkably slim, and playing the sport at the professional level strongly correlates to major illness early in life. The league’s most recent collective bargaining agreement with the players stipulates that a player needs to accrue three full NFL seasons to become eligible to collect a pension — the pension kicks in at age 55 and averages between $30-46,000 per year. Not exactly a golden parachute.

Baseball is similar in some ways but much better in others.

First and foremost it’s much (much) easier on the body. Players play longer, have longer periods of earning potential, and contracts are largely guaranteed. But, as with football, and basketball for that matter, most players will never make tens of millions of dollars. In fact, most professional baseball players will never set foot on a major league field. According to Baseball Almanac, there have been a total of just under 21,000 major league baseball players all time. This is going back to 1876. For perspective, Yankee Stadium has a capacity of 46,537 — if you put every player who has ever been a major leaguer in the stadium it would not even be half full. In short, it’s nearly impossible to become a major league baseball player.

This winter, the Los Angeles Dodgers signed the best player on the planet, Japan-born Shohei Ohtani, to an unprecedented 10-year $700 million contract. A couple of weeks later those same Dodgers landed Japan’s best pitcher, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, on a $325 million contract. These are gaudy figures — outlandish really. They are also complete aberrations. For every player making more than $20 million per year in the majors, there are hundreds of minor leaguers making somewhere between $5,000 and $40,000 — and even the $40,000 earners are rare.

To boot, the conditions in minor league baseball just recently changed with a new labor deal. Major League Baseball — which is to say, team owners — had successfully lobbied Congress for decades to exempt minor league players from minimum wage laws. These are guys who are grinding, following their passion (remember what it means when you tell your kids, your nieces, your nephews to do that), and putting in impossible hours to hone their craft… and then doing a shift at Home Depot to make ends meet. Here’s a very telling story from now-defunct 538 that paints a vivid picture of “the life.”

Corporate executives routinely make more money than even the highest-paid professional athletes, and middle management at a successful Silicon Valley company is a much more financially lucrative life than choosing to pursue professional sports. Some of the parachutes and stock deals in the corporate world make even Ohtani’s deal look pretty run-of-the-mill.

Taken together, professional sports are a great example of class warfare. Owning a major professional sports team is a winning proposition across the board. Go here and look at the chart — between 2018 and 2022, not one single major league baseball team lost value. The Yankees are worth more than $7 billion, up more than 54% over just that 4-year stretch. The median increase in value is 25% across the league in that time frame and there isn’t a team in the league worth under $1 billion.

Owning an NBA team is somehow an even better investment. There isn’t a team worth less than $1.5 billion and the median growth in franchise value between 2016 and 2021 was 45%. That sort of wealth creation is unheard of — unless you look at the valuations and growth of NFL teams. Between 2016 and 2020, no team — NOT ONE — increased in value by less than 61%. Financial managers would kill for returns like that on multi-billion-dollar investments, and I don’t think it’s out of turn to pull for athletes to make as much money as possible, in fact, that’s where I’ve landed on the whole thing.

Every time you hear “these millionaire athletes,” remember that most of these athletes you’re seeing are decidedly not millionaires. The people paying them — often the same people trying to get public funding for new stadiums — blew past the “millionaire” label years ago. And, of course, things are much, much worse for professional women’s sports in the U.S., with the most popular women’s league, the WNBA, having a minimum salary of just $62,000.

Every time you see a headline about an absurd amount of money going to a star athlete, maybe a nice little “good for them” is the way to go — I know that’s where I’m at.

— Sree

Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn | YouTube | Threads

DIGIMENTORS TECH TIP | CES 2024: AI, AI Everywhere

By Robert S. Anthony

Each week, veteran tech journalist Bob Anthony shares a tech tip you don’t want to miss. Follow him @newyorkbob.

Las Vegas is all about the Super Bowl now, but a few weeks ago it was blanketed with countless electronic gizmos and technologies as CES, the consumer electronics mega-showcase, enveloped the city for a week. For 2024, the key words were “artificial intelligence” and there was no shortage of clever uses for the evolving technologies.

This year marked an attendance comeback for CES with more than 135,000 attendees filling the Las Vegas Convention Center and other venues, according to the Consumer Technology Association, which operates CES. No, it didn’t match the 170,000 from pre-pandemic CES 2020, but marked a significant improvement over the 115,000 that saw CES 2023.

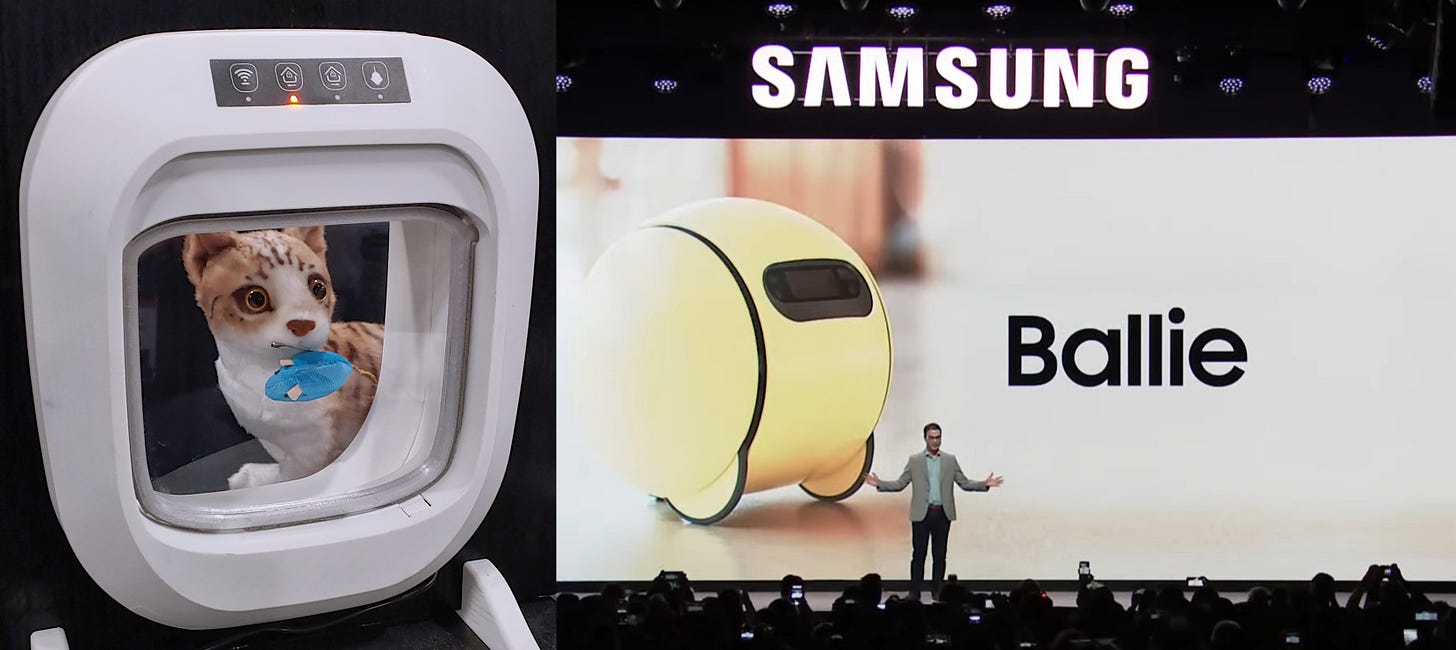

Samsung saved its smartphone announcements for after CES, but in Las Vegas it highlighted its advances in AI, including a preview of a new version of Ballie, a rotund, rolling “AI home companion robot.” The unit, about the size of a bowling ball, not only contains a camera, speaker and a microphone, but also incorporates a projector and can show movies or images on floors, ceilings or walls.

According to Samsung, Ballie uses AI to learn a user’s habits and patterns and can patrol a home on its own, sending notifications to a smartphone app as needed. In a video shown at Samsung’s CES press conference, the unit catches a dog making a mess and sends a notification to its owner, who then instructs Ballie to dispense food from a smart pet feeder.

However, like an earlier Ballie prototype shown in 2020, Samsung offered no details on the specifications of the unit, pricing or when it might become available.

Smart pet doors are nothing new, but AI can help your home from being the final resting place for “presents” brought home by the family cat. At CES, Switzerland-based Flappie Technologies, founded by twin brothers Denis and Oliver Widler, showed off Flappie, an AI-assisted cat door which incorporates “prey detection.”

If your cat comes home with a dead bird, rodent or other “gift” in its mouth, Flappie’s camera will recognize the prey, send a notification to a smartphone app and keep the pet door locked. When the cat returns with nothing in its mouth, the door will open and lock as usual. The unit can read microchips, thus ensuring that only your cats can use the door.

According to the company, the AI-powered prey detection can recognize numerous breeds of cats and prey. The unit can keep a video record of a cat’s comings and goings, thus giving its owner insight into the cat’s behavior patterns. Flappie is expected to be available this spring first in Europe before making its way to the US, according to the company.

Watch this space for more coverage of products at technologies seen at CES 2024.

Did we miss anything? Make a mistake? Do you have an idea for anything we’re up to? Let’s collaborate! sree@sree.net and please connect w/ me: Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn | YouTube / Threads

Great column, and you make an excellent point: Football players work really hard.

A comment on the lighter side: My 5 and 8-year-old grandsons are fixated on football right now and dream of being football players. No other sport really interests them either to play or watch. (The 5-year-old did say this weekend that he wants to be a football "commenmentor" more than a player.) When the 8-year-old talks about all the money football players make, the adults around him tell him he'd make more money as a baseball pro, so maybe he should consider doing little league instead of another session of football.

An observation that's not funny at all: Pro football players choose to do this. They go into this knowing they're likely to get hit and that every game can be punishing. The best get tremendous rewards for doing something totally brutal. The crowd loves all the hits and the drama of injury. Maybe there is something wrong with us that we shell out money and that networks shell out money so that people can watch grown men beat each other up. I feel the same way about boxing, btw.

Also about minor league baseball players: They are such heroes. I have never seen so much devotion to playing a sport as I see when I attend minor league games (which is pretty often). Up close . . . well, sometimes the players make, from a viewer's vantage point, pretty dumb plays. But then all you have to do is take a breath and it comes to you that these guys are amazing athletes, so much better than 99.9999999999999999% of us could ever be.

One more thing: Didn't the basketball leagues have a tournament early on this season, and the reason the tournament meant so much to the highest-paid pros was that everyone on the teams, the bench warmers, etc., made something like 800K? And doesn't this happen in pro soccer also?

BTW, there was an essay in the Little, Brown Handbook Grammar in the 1970s that was about how pro athletes worked for their money. I'll scan it and send it to you.

Many thanks for your thoughtful reply, Zach. Your point on personal taxes and, you might add, expenses of athletes provides an important economic frame to this discussion. What I believe is not being discussed enough -- and could be a powerful foundation for a book-length exploration of the aspirational elitism of American culture, something massively, if not grotesquely on display in Sunday's Super Bowl game, is the human impacts on a community. Then all of your financials fall into place, that is, to strengthen, and not supersede in dollar-sign minutia, the emotional and ethical effects of what passes for sports culture. I'm thinking of how every time a young star seems to suddenly rise with success, media will go to the standouts home town or neighborhood for spot interviews with the high school or college coach, friends, neighbors -- you know the drill. But I'd love to see someone really dig into the actually personalities and social-economic structure of the place. What does the wide-eyed hopefulness around the young star expose about the lives of his or her community? Well, yes, I'm thinking of early Joan Didion piece for The New Yorker, and so on. But just for your work, have you spent time in a community like that to talk to people about what their new beacon's success means to them and the place where they live?